by Rory Morgan

In 1864, a semi-fictional book entitled Red-Tape and Pigeon-Hole Generals appeared. The author remained anonymous, simply calling himself "A Citizen-Soldier". It used dark humor and thinly-disguised characters to blast the “ . . . drunkenness, half-heartedness, and senseless routine . . .” among the officers of the Army of the Potomac, the Union’s most well-known fighting force.

The book was particularly critical of Union general Andrew A. Humphreys - portrayed as "Old Pigey" in the book, - for his drinking and his harshness as a commander. Humphreys was a career soldier; a “Regular”, as they were called in the Civil War. He was a Philadelphia native from a prominent family. He had attended the quasi-military academy of Nazareth Hall and then the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, NY, graduating in 1831. He spent most of his pre-war career in the Army’s Corps of Engineers. It turned out to be an ideal place for him in peacetime; he served there until the outbreak of the Civil War. His work was mostly in surveying, mapping and scientific work. It did not include any significant combat experience, nor did it include leading any significant numbers of soldiers.

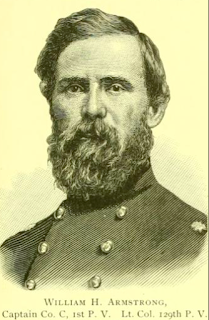

The book's author was eventually determined to be an Easton attorney, William H. Armstrong. He was a Lieutenant Colonel, serving as second-in-command of the 129th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry regiment. Armstrong was a native of the Lewisburg (PA) area and came to Easton to study law. When his education was completed, he stayed in Easton and began practicing law. He was active in one of Easton’s several pre-war militia units, the Easton Invincibles. When the Civil War erupted in April 1861, he helped to recruit the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry regiment, which had several companies of Northampton County men. (Companies, identified by letter, were units of approximately 100 men; ten companies made up a regiment.)

The commander of the regiment, with the rank of Colonel, was prominent Easton citizen Samuel Yohe. Company captains from Easton included Armstrong (commander of Company C), Jacob Dachradt, Charles Heckman, and Ferdinand Bell. Like most of the early Union volunteer units, the 1st Pennsylvania was a three-month regiment; virtually no one on either side anticipated a war that would last for years. The regiment’s short service, from April to September, was uneventful. After 90 days, its soldiers, including Armstrong, were “mustered out” to return to their homes. They were now veterans.

By the summer of 1862, the war was not going well for the Union; the Army’s need for additional manpower was obvious. New Pennsylvania regiments, to serve for nine months, were recruited in Northampton and other counties – one was the 129th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Armstrong helped to recruit soldiers for the new regiment. Many of them were veterans of the old 1st Pennsylvania; they now patriotically signed up for a second tour of duty). Armstrong became second-in-command of the regiment, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. The 129th was assigned to the 3rd Division of the 5th Corps. which was under the command of Humphreys.

Soon after the regiment was organized, it was dispatched to Sharpsburg, MD, where the Battle of Antietam was under way. The regiment’s arrival was, however, just a bit too late to participate. So, its initial combat experience was at the Battle of Fredericksburg (VA), in December of 1862. The battle was a disaster for the Union troops, poorly planned and poorly executed, The 129th was among the many regiments ordered to attack uphill; the Confederates at the top were sheltered behind a stone wall. As might be expected, casualties were heavy. Armstrong’s horse was shot from under him during the battle. (The citizens of Easton later presented him with a new horse.) Six months later, at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Armstrong was twice captured, quickly escaping both times.

Away from the battlefield, there was consistent tension between General Humphreys and several of the volunteer officers under him, including Armstrong. The tension was aggravated when Armstrong, no stranger to a courtroom, successfully defended an enlisted man in a court-martial proceeding initiated by Humphreys. In the spring of 1863, the tension finally erupted in the so-called “frock coat mutiny." Frock coats were heavy Army dress coats, primarily used for parades and other formal occasions. For whatever reason, the soldiers of the 129th did not have them, so, in early 1863, the Army issued orders requiring them to “draw” frock coats. In line with Army policy, the coats would be charged against the soldiers’ uniform allowance; if there was not enough money in a soldier’s account, their regular pay would be charged.

Armstrong, joined by his superior, Colonel Jacob Frick, thought that the expense was unnecessary, in view of the fact that the regiment’s enlistments would expire in the spring, and that the coats would add to the burden carried by soldiers on the march. Suspecting that the Army was trying to bail out a contractor who was stuck with excess inventory, Frick and Armstrong applied for an exemption to the requirement - but General Humphreys refused their request.

Planning to appeal Humphrey’s decision, Armstrong and Frick didn’t issue the necessary requisitions for the coats. The General then filed charges against Armstrong and Frick. He had them arrested and held for a court-martial. Armstrong, in particular, seems to have been held in abysmal conditions. Following the trial, he and Frick were “cashiered",meaning that they were dismissed from the service. Soon however, the two officers were reinstated to their ranks and positions; they completed their service on May 18,1863, when they and the rest of the 129th were mustered out.

After that, Armstrong was appointed Deputy Secretary of the Commonwealth by Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtin. Eventually, he returned to Easton to practice law. But, as one of the county judges noted in a memorial when Armstrong died, “Many of his old clients were dead and the rest were scattered . . .” He wasn’t able to rebuild his old practice to its previous level.

His service not only caused significant damage to his professional life, but also to his physical condition. The decline in his health, blamed on the conditions under which he was held while under arrest, culminated in total blindness during the last two years of his life.

Armstrong died on April 7, 1896 and is buried in Easton Cemetery, Plot C-173. His wife, Myra Chidsey Armstrong, and their three sons survived him.